Altitude sickness

This is a photo of Dr Nikhil Rastogi, director of undergraduate anesthesia at the Ottawa Hospital in Canada. It was taken last year at Cotacachi Hospital in Ecuador, where Lifebox donated a pulse oximeter through Medical Ministry International.

He seems quite healthy, but look at the Lifebox pulse oximeter (and the knowing smile) he’s wearing: 92% oxygen saturation.

Anything higher than 80 out of 100 on a test is a pretty high pass, but when it comes to oxygen saturation, anything lower than than 95% is a concern and 80% is a crisis situation. If Dr Rastogi wasn’t wearing a pulse oximeter you’d have no way of knowing that his oxygen saturation is not at the level it should be.

This is the blindfolded reality that anaesthesia providers in more than 77,000 operating theatres worldwide face every day. The only way they can tell if a patient is becoming dangerously hypoxic (starved of oxygen) is by close observation for signs of cyanosis – when the patient’s skin starts turning blue.

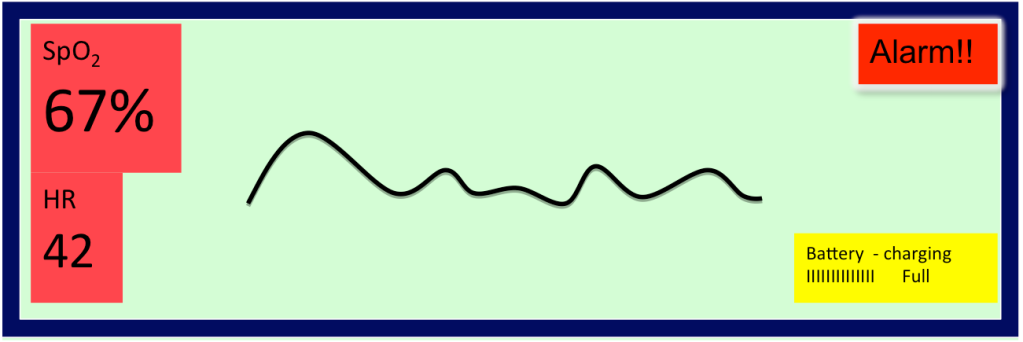

When we’re training anaesthesia providers in pulse oximetry and the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist, we focus on the fact that the Sp02 (oxygen saturation) for patients of all ages should be 95% and above. When the Sp02 falls below 90%, the patient is becoming dangerously deprived of oxygen.

In low-income countries, oxygen cylinders can sit empty for months; many of the critical therapies that we take for granted just aren’t an option. Early identification of a problem makes successful intervention, with the limited resources available, much more likely – pulse oximetry monitoring, quite obviously, saves lives.

And please don’t worry about Dr Rastogi – Cotacachi Hospital is at 8000 feet above sea level, and he’s just acclimatizing to the altitude!