A Presidential COSECSA conversation

The risk is high: an invisible threat to patients who’ve given everything they’ve got to get to a hospital, reversing the life-saving work of surgical teams striving to save them. Our Clean Cut programme, piloting in Ethiopia, aims to develop simple and scalable inventions that use training, monitoring and evaluation to make surgery safer.

We were lucky enough to catch up with Prof Derbew at the West African College of Surgeons meeting in Cameroon earlier this year, and get some of his expertise on paper.

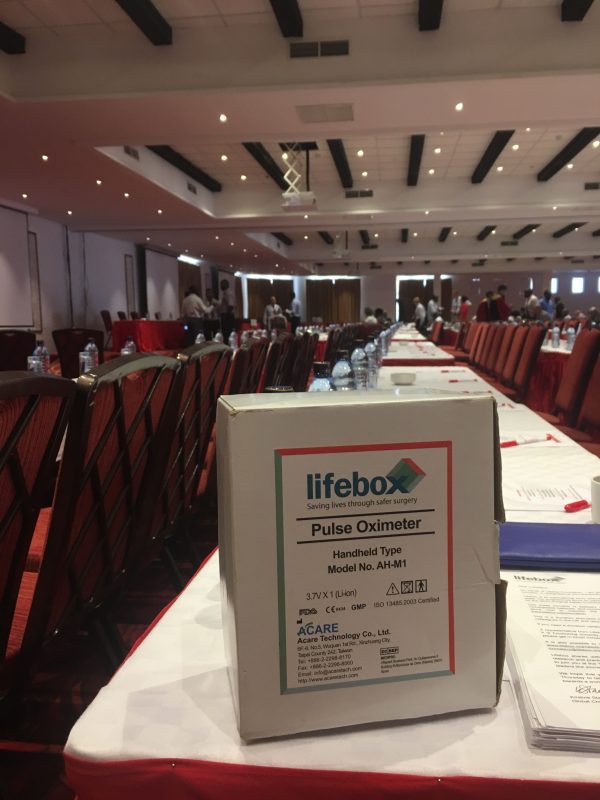

Why did you get involved with Lifebox?

I agreed that the time had come to stop talking about pulse oximetry – and to do it.

It’s not something that’s optional, it’s a necessity – especially in low-resource countries where hospitals have very limited life support, limited ICU care, limited professional staff or access to skills training. The value of pulse oximetry in this environment is indispensable.

Pulse oximetry is often seen as an anaesthesia tool, as a surgeon has the scalpel. Do you think surgeons recognise the importance of oxygen monitoring?

You can’t work without it. Doing surgery without pulse oximetry is like navigating in the dark without any navigation materials – but its someone’s life on the line.

A small surgery can be done perfectly, but the airway issue may not be under control. And previously the parameters we had for identifying hypoxia or ventilation problems were so broad that the patient could be on the verge of death. Now, using a pulse oximeter, you can immediately can pick up the danger.

How does the early detection system help save lives?

In paediatrics you get a lot of children coming in with foreign body aspiration. They quickly become hypoxic, but our bronchoscope doesn’t allow for simultaneous extraction and ventilation – so we pre-oxygenate, counting to 100.

But extracting a foreign body from a small child is not as simple as going in and taking it out! You make multiple attempts, and sometimes you stay longer. By the time you remove the obstruction, the child is already hypoxic.

We have lost so many children because of hypoxic brain damage – they’re small, and they desaturate so quickly.

Is there a specific case that’s on your mind?

I remember a child who was operated on for a cleft lip, and the surgeon forgot to take out the gauze used to keep the site clear.

The boy was struggling to breathe, but nobody picked up how severe it was. Finally they noticed there was a foreign body in his mouth and and sent him back to the OR, but it was too late. He suffered severe brain damage and died soon after.

But now we have pulse oximetry, we’re much more comfortable. We can see when the saturation is 100% – and when it starts going down, we can pull back and and re-ventilate.

Lifebox’s pulse oximetry work in Ethiopia will bring a big change to morbidity and mortality.

You’re helping to develop Lifebox’s pilot project around reduction of surgical site infection. What drives your interest?

You can go into any operating room in the world, look around and think ‘this place is prone for infection’. But in Africa it’s much more complicated than that. Infection is associated not only with bacterial load or pathogenic organisms, but with the conditions of the environment itself.

For instance the majority of our operations – perhaps 60% – are emergencies. Most our patients are rushed to theatre and aren’t properly prepared for surgery, so that’s a risk factor.

Then there are the delays in operations – long waiting lists, more complicated cases, which lead to longer recovery times and increased exposure to infection. And environmental factors extend far beyond the hospital. Most of our patients are malnourished, especially school children or those from the countryside. And of course that’s a precondition for infection.

It’s something we have on our mind all the time.