The Professor who put an oximeter on the Checklist

Decades earlier, Professor Soyannwo’s son was born by emergency C-section, without oxygen monitoring. His brain was deprived of oxygen, and helives now with the long-term effects of prolonged hypoxia. Pulse oximetry monitoring could have changed his life. And in sharing her son’s story, Professor Olaitan made the case for pulse oximetry, changing the Checklist, setting the stage for Lifebox – and changing thousands of lives.

Did you go to Geneva expecting to tell such a personal story?

Did you go to Geneva expecting to tell such a personal story?

No, no – it certainly wasn’t planned. I was so surprised that I even came out with it, because I don’t normally talk about my son in public, in large groups. But we had earlier on been talking informally about family before the meeting, and you know how it goes – oh you look younger than your age, do you have kids, how many girls, how many boys, and where are they now.

At the meeting, I listened to the way people were arguing, talking about the importance of water, electricity, infrastructure – because they had worked in Africa or other low-resource countries. And they were trying to show that there are issues more important than monitoring.

Is a pulse oximeter more useful in surgery than infrastructure?

It’s true that water and electricity are problematic areas – but we’ve always had to manage resources in surgery. That’s for your management of the hospital to sort out. But when it comes to anaesthesia, that’s a one-to-one problem. Once you accept to anesthetize a patient, you’ve taken the responsibility.

I sat there quietly in Geneva, listening, and thought – do these people really know what they’re talking about? I worked in a hospital all my life, and in return I got a son who suffered oxygen deprivation. And now I’m looking after him, and living with it. That’s what prompted me to speak.

What happened during the birth of your son?

I was a young doctor, and I was having my first baby at the hospital where I worked. In those days there was hardly any monitoring, just an earpiece to hear the baby’s heart. So the C-section came too late, and my son was severely asphyxiated. They resuscitated aggressively – it would have been unheard of, for a young house officer to lose her baby.

But down the line, I knew something was wrong.

How did you convince the Checklist consulting group in Geneva to include the oximeter?

I just told them that oxygen deprivation can be devastating. Not just immediately, but even worse in the long term. I don’t have a support system in my country. So I have to bear everything about my son’s care within my family.

We anesthetize people, and once they wake up we’re happy; we may never see them again. But then months, years down the line there may be things they suffer. And that’s when my son came to mind. It was spontaneous.

When I finished talking, the whole meeting just went silent, silent. And then there was applause. I still remember vividly, and I think I will always remember. I’ve been a teacher all my working life – I wasn’t nervous. But that’s the first time I talked about my son publicly. And not at just any meeting: at a high level international WHO meeting.

I’m so happy it did what it did. And I’m happy Lifebox is getting on fine.

Are you surprised about how far the pulse oximeter has spread?

Are you surprised about how far the pulse oximeter has spread?

I won’t say I’m surprised at how the work has developed, because of the drivers behind it. Because I know that it’s not about making money: there’s passion, there’s interest in making things better globally. It was one of the best teams I’ve worked with.

Transparency and commitment: that’s what yielded dividends, and this work is life-saving. It’s not just restricted to surgery and anaesthesia – a pulse oximeter can help anyone in critical condition, fighting for life.

What is it like for the anaesthesia provider, working in unsafe conditions?

I got passionate about it because I remember the way we were practicing in my country. Because it was the most advanced tertiary institution, we were handling all the major cases, and it used to be a nightmare. There was no monitoring equipment, and it was just too stressful. When the patient is under anaesthesia your own heart rate is constantly going up; it’s like working in a dark tunnel. Stress is violent on your own body. Your brain is suffering, your heart is suffering, you can feel it – your whole body, after a major procedure. You find that you can’t sleep for days because you are worrying about that patient.

When I see surgery on the news, there’s always a lot of noise around the surgeon – like a recent case in the U.S., separating conjoined twins. But did you hear a word about the anaesthetist? I heard the word team, ‘the surgeon and his team’. I never heard the word ‘anaesthesiologist’.

What are your hopes for the WHO Checklist, ten years on?

What are your hopes for the WHO Checklist, ten years on?

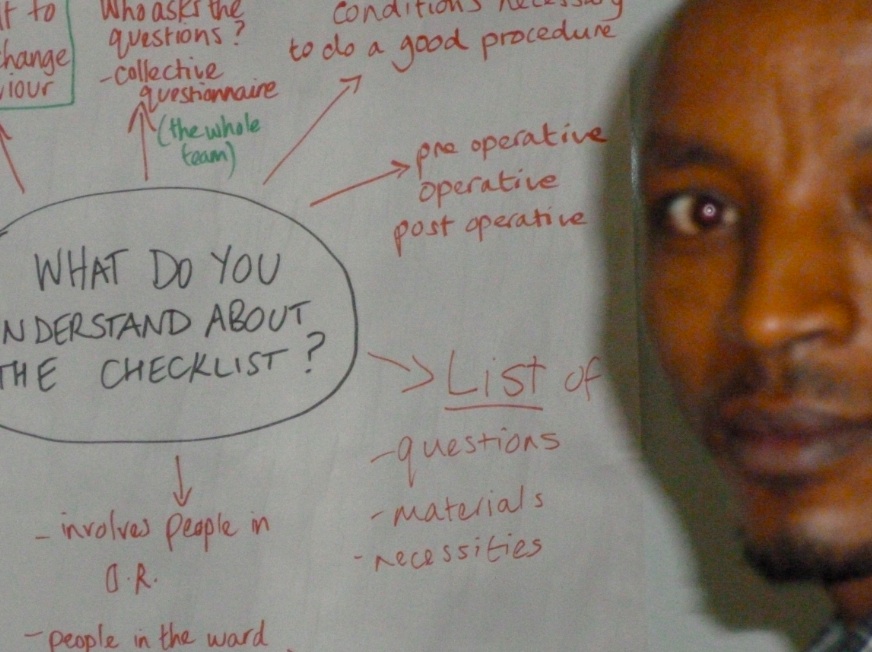

It’s a very good thing to have in place, but the problem is always implementation. So you learn from experience. You need cooperation to make it work – and attitudes are always difficult to change. You introduce it slowly, you hope people will develop interest.

This interview was conducted at ANESTHESIOLOGY 2016, in Chicago, U.S.A. Lifebox caught up with Professor Soyannwo again this week at the 6th All Africa Anaesthesia Conference.