Science without borders, numbers with intent

Gymnastics in service of illustrating a point (and charming the crowd) during his keynote speech at the Médecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) Scientific Day in London last Friday, and he’s waving his arms enthusiastically.

Intelligent data can do that – draw insight and outrage from dense statistics, and make you want to stand 10 feet tall so people can see what you see.

For instance a better view of the impossible equation facing the ministry of health in Vietnam today, which Hans challenged the audience to balance: a disease panel equivalent to America in the 1980s divided by the resources of the U.S. economy in the 1960s, multiplied by popular demand for 21st century technology.*

Answers on a very large postcard. Please.

Or the view from Lagos State, Nigeria, where the maternal mortality ratio is 545/100,000 live births (one of the highest in the world, compared with 8.2 in the U.K., 16.7 in the U.S.). That’s bad, but sub-regional data focuses the binoculars, and it gets much worse: MSF research has shown that in two of Lagos’ urban slums, the ratio is nearly double – a sinkhole of a crisis unseen except by those who are falling in.

Responsive and responsible statistics can give vulnerable populations a table to stand on, and global health workers a more effective place to begin. They can help allocate resources and advocate for change.

In other words – heck, in Bill Gates’ words! – measurement matters.

So say the professionals – so says Lifebox – and so says MSF, whose Manson Unit aims to use medicine, lab work and epidemiology to identify developments in the management of medical issues and help MSF field projects to put these changes into practice.

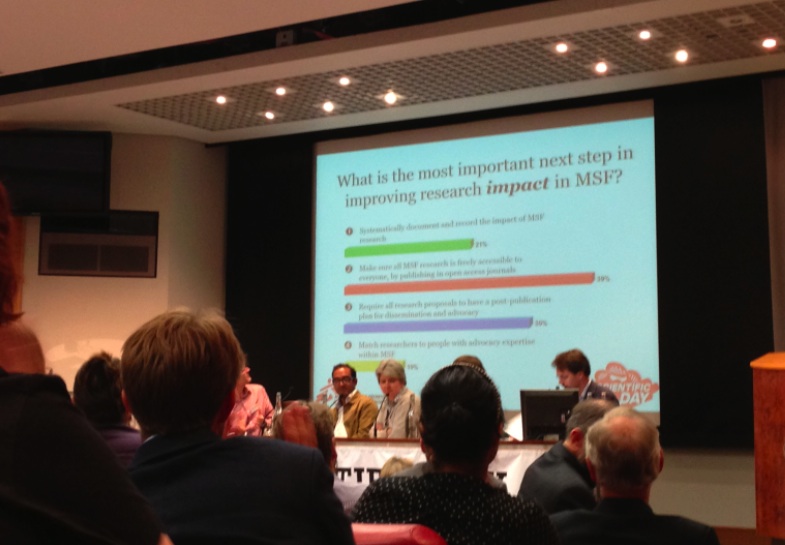

And our audience survey says:

Make sure all MSF research is freely accessible to everyone, by publising in open access journals (39%)

MSF has been presenting research findings at its yearly scientific conference since 2004 (holy archives!) and seems to aspire to a central message: to make a useful impact in global health, we have to listen.

Listen to patterns, listen to colleagues, and most obviously listen to the needs of those groups we are trying to support against a vastly unequal setup.

“Do we actually know the people in the refugee camps? Do we know their needs?” asked Philipp du Cros, head of the Manson Unit.

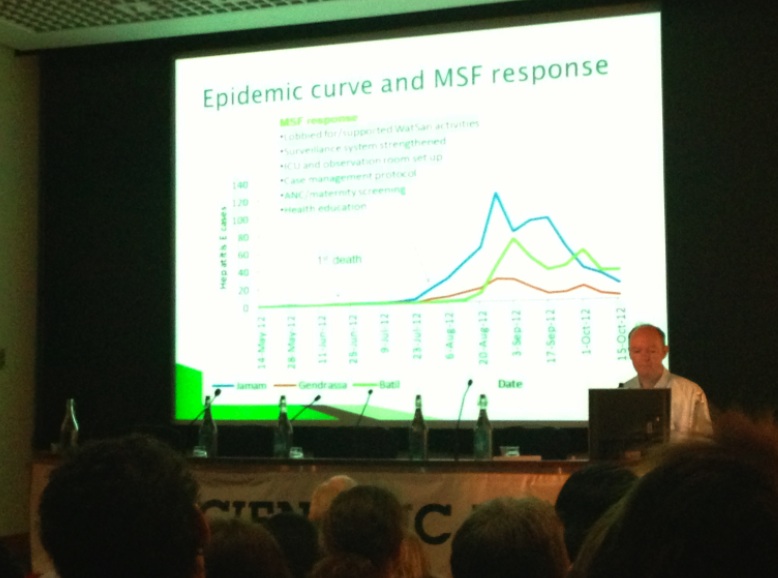

For MSF, this has most recently meant investigating reports of excessive deaths in young children in Zamfara State, Nigeria, and joining a multi-agency response to treat the lead poisoning caused by small-scale gold mining; implementing a voluntary reporting system for medical errors in its projects to improve systems (such as increased use of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist) without allocating blame; following up on reports of death due to ‘yellow eye’ in South Sudan and acting to address the Hepatitis E outbreak (often first identified by acute jaundice), in real time.

Open access was a happy feature of the day, with support from PLOS (the Public Library of Science), dynamic Twitterlogue, and all presentations available online here.

Even more boundless was the audience that followed online, joining in the conversation via live streaming from 92 countries wordwide.

The boundaries between research, advocacy and resources are blurry, and objectivity requires a stance that doesn’t leave much room for compromise. So there was criticism on Friday, too, but that wasn’t our takeaway message.

The primary concern of any global health initiative needs to be a constantly renewed understanding of the reality of the situation, so that we have a chance of successfully addressing it. If we don’t ask, regard, review, how do we know?

There are a lot of people listening. Let’s ask them.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

*See Hans Rosling’s 2006 TED Talk, ‘Stats that reshape your worldview’. And his curated 5 TED Talks on global issues here. And his conversation with Partners in Health. In fact, why don’t you go for a Rosling ramble – good for your circulation, and we’ll be right here when you get back.