The humanity in humanitarian

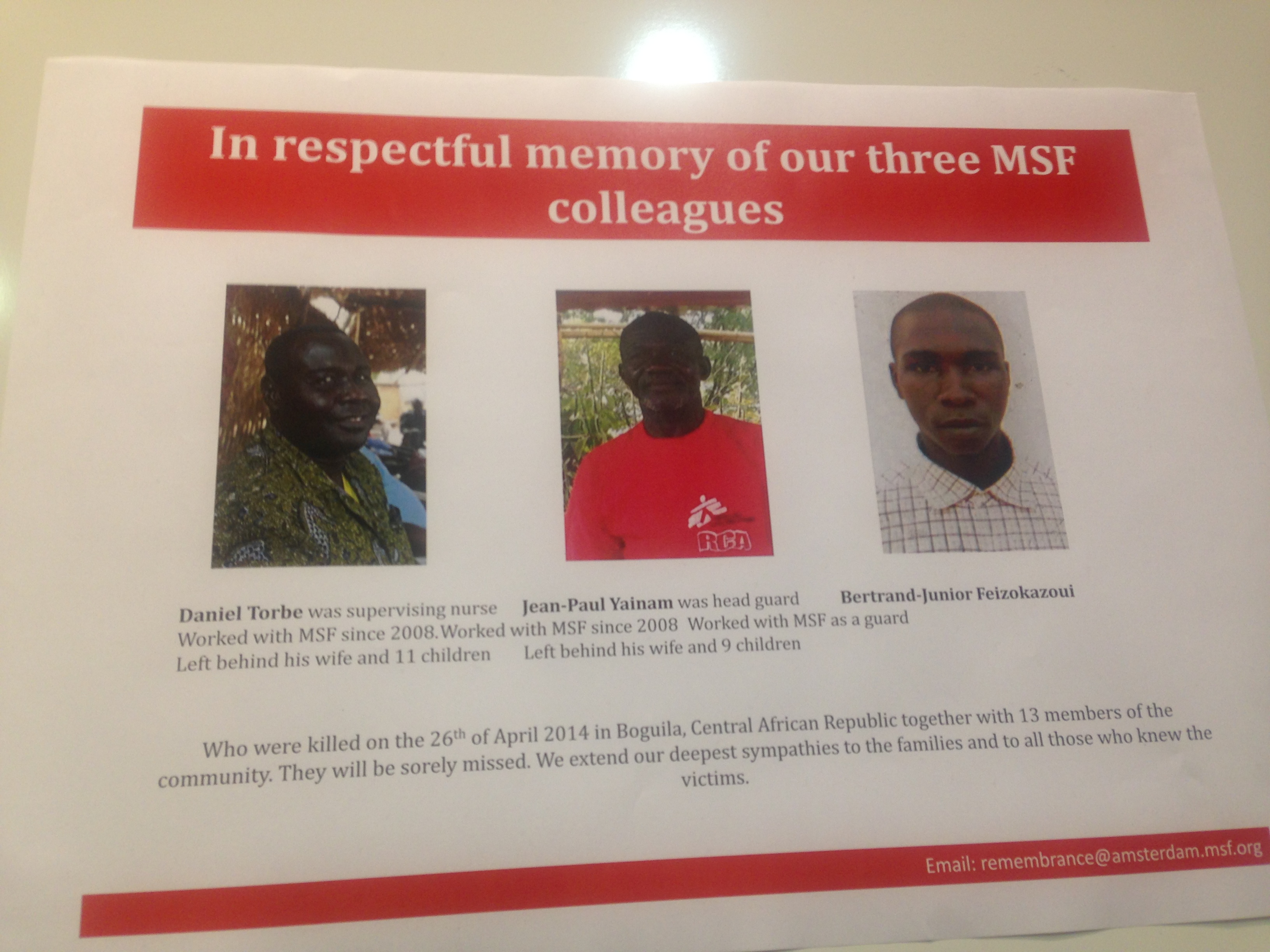

But what else could they do? It’s the 20th anniversary of the Rwandan Genocide, when MSF concluded that “you can’t stop genocide with doctors.” The current situation in Central African Republic (CAR), Syria and Somalia is devastating, with MSF losing colleagues and in some cases having to pull back for the first time in 22 years.

How do you stand in these shadows and talk about humanitarian aid without asking the question: how far has it really moved since then?

“Collectively we need to do better,” said Vickie Hawkins, General Director of MSF UK. “We need to find new methods.”

New methods, and age-old priorities. If last year’s conference put the spotlight on measurement (from Hans Rosling‘s great table height) the focus this year seemed to be on the faces and the hearts behind it.

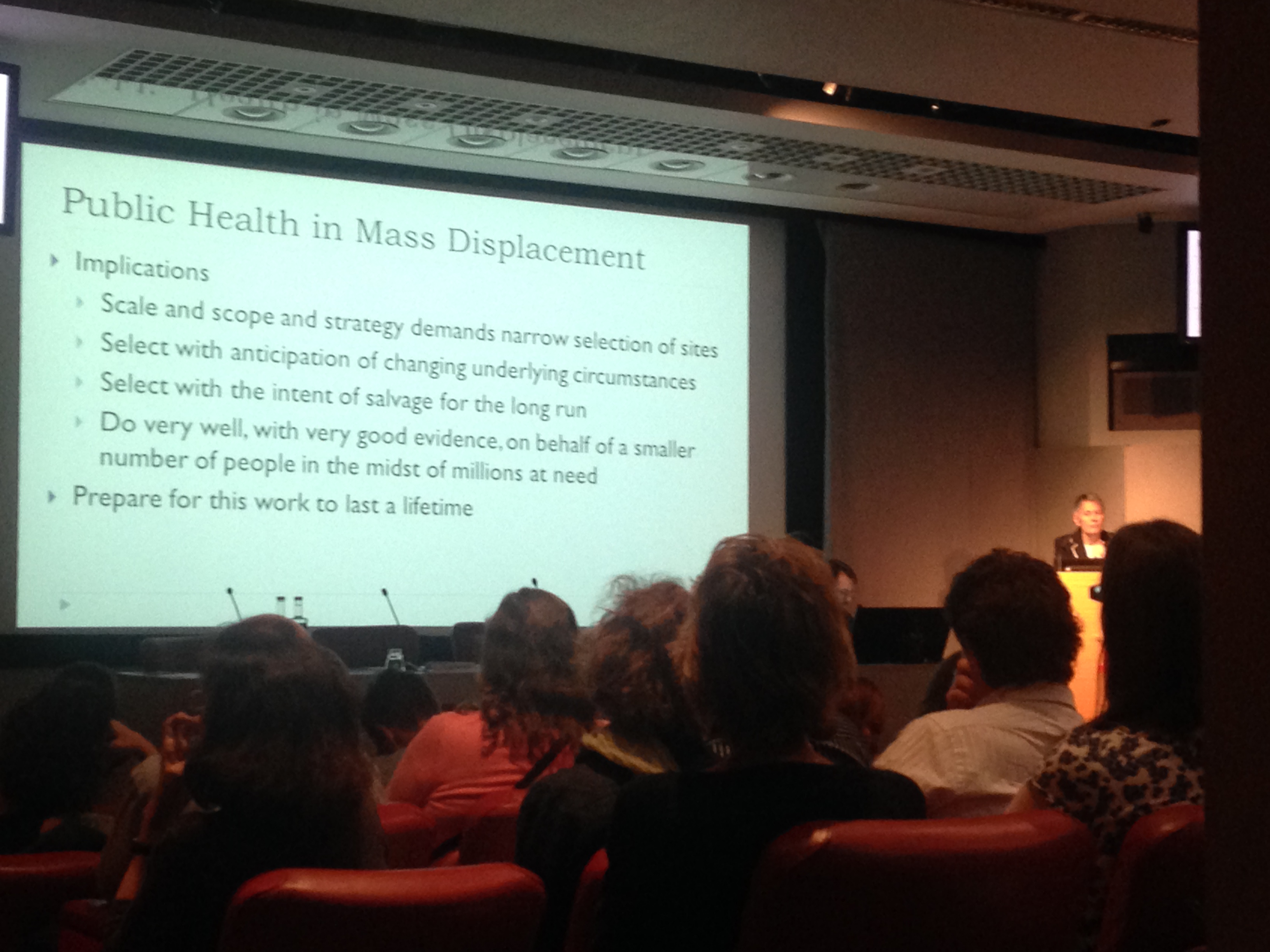

Keynote speaker Jennifer Leaning, director of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights in Boston, gave a powerful talk about the role of evidence in humanitarian decision-making, challenging the audience to put humanity at the centre of it.

“Respecting their biography is as important as the immediate healthcare you can provide,” she said, of her experience working with refugees. “And prepare for this work to last a lifetime. The point is not to keep people alive, but to help them live.”

With presentations on subjects ranging from “health services for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence in Papua New Guinea” to “tech solutions for understanding the who, what and where of the needs of populations in crisis,” panelists regularly concluding with thanks to their colleagues still on the ground and more than 2000 viewers watching online across 108 countries, there was a strong sense of wanting to make the day more than an echo chamber for clean data.

Because publications in size 12 font may keep the stories straight, but there’s a lot more to be said – and learned – from breaking silos.

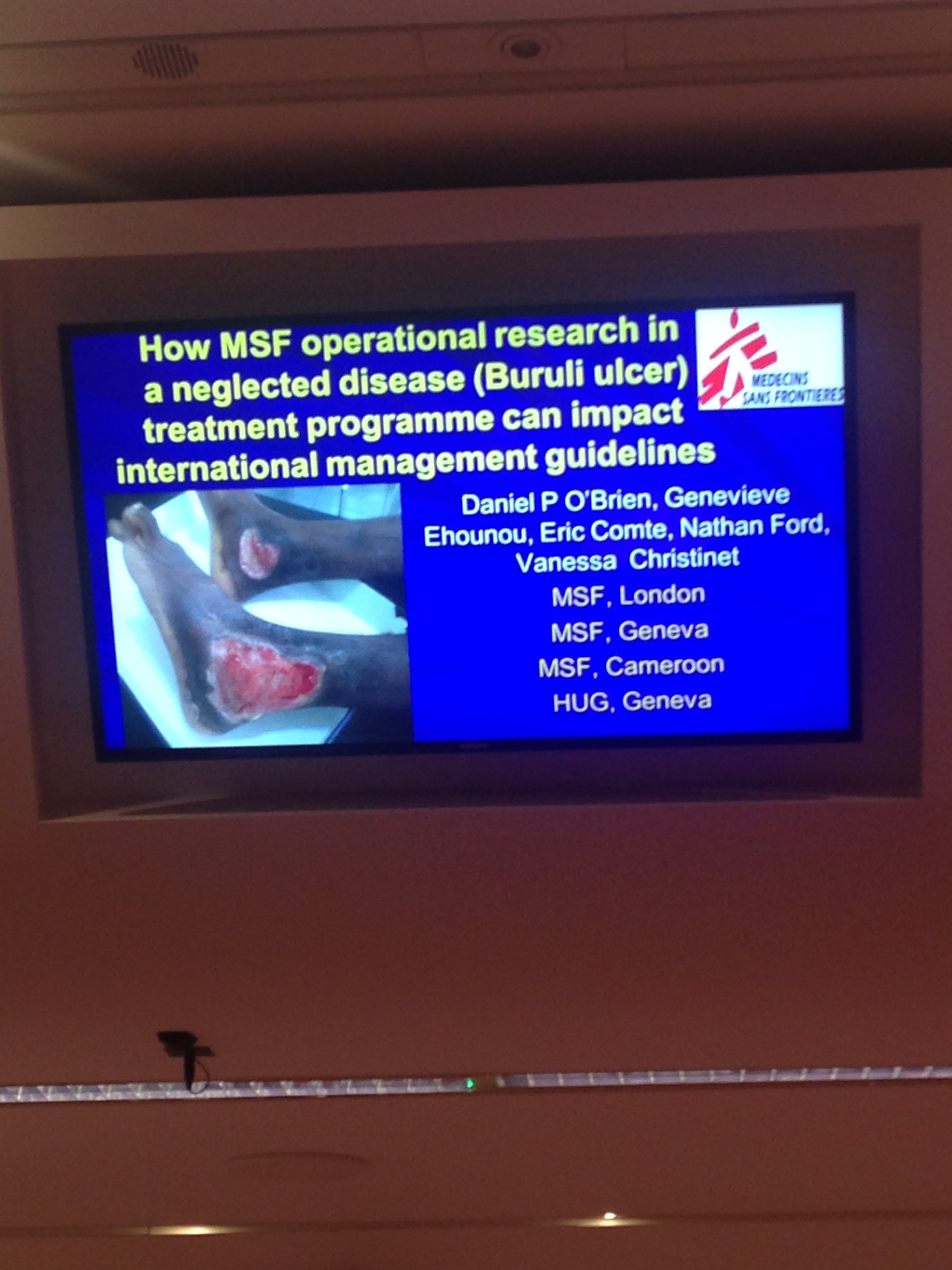

Take the Buruli ulcer, an infectious disease that can damage right through to the bone, and is present in countries where HIV is prevalent. How do the two conditions interact? How does this shape international guidelines?

Take the Buruli ulcer, an infectious disease that can damage right through to the bone, and is present in countries where HIV is prevalent. How do the two conditions interact? How does this shape international guidelines?

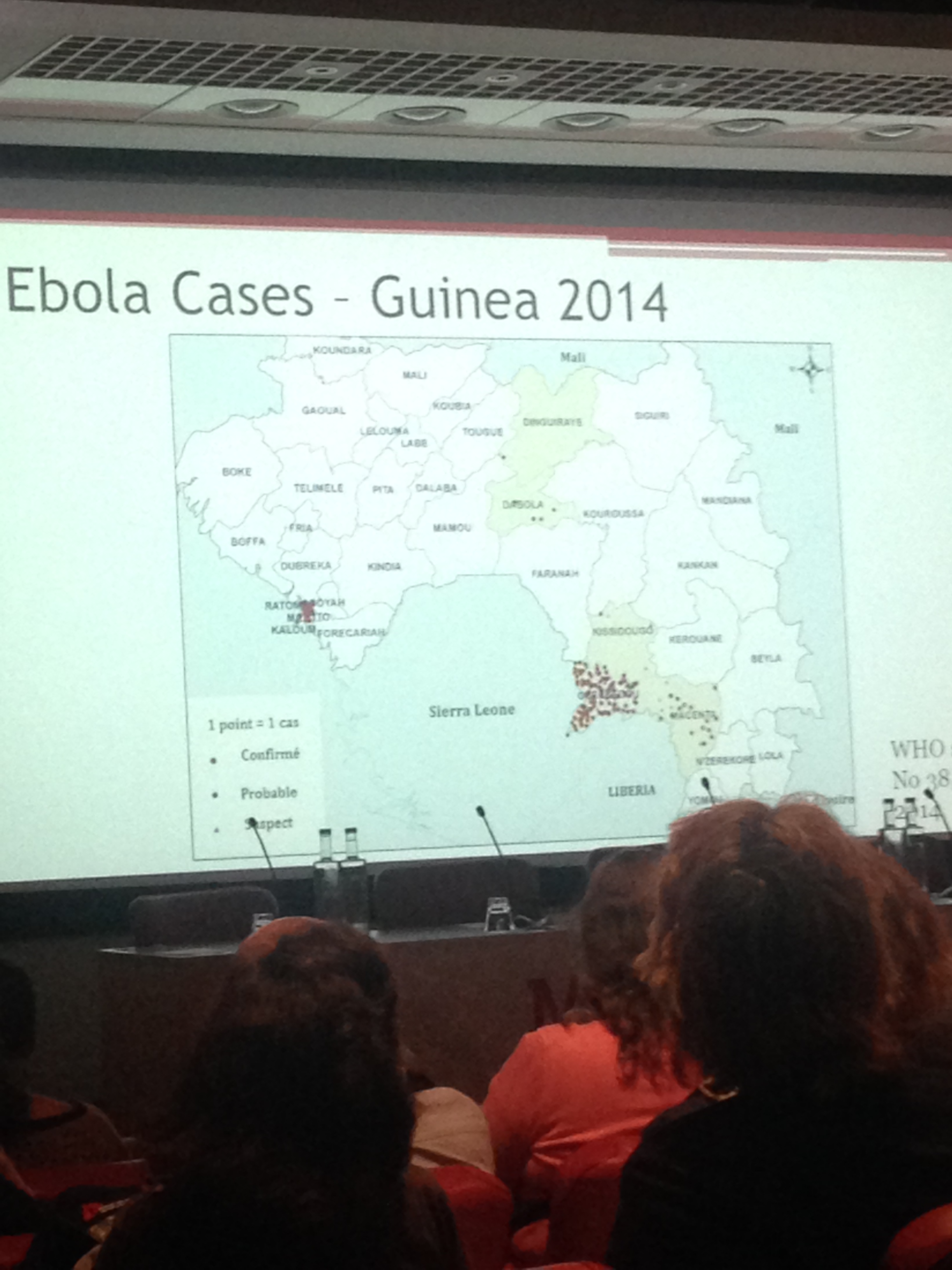

Why were hiccups more frequent during hospital stay for Bundibugyo Ebola virus than self-reported at admission? What do we learn when we distinguish between food security and nutrition security?

Nothing is in a vacuum, and again and again we put our hope in the equation that the more questions we ask, the better our questions get, and the closer we get to answers.

Like a late-breaking session on how to deal with the current Ebola outbreak, the 6th (or 4th) largest on record.

“What’s the problem?” asked panelist Armand Sprecher, devil’s advocaliciously. “This is Ebola, we’ve done this before.”

Well, he explained – you need the treatment centres, and the outreach to go find patients and bring them back. You need to trace how they got sick and who they’ve been in contact with, and follow up with those contacts for two days. You need to bury your dead safely, undertake health promotion in the community, engage with local providers so they can identify suspect cases, participate not obstruct…

“Epidemics,” said the German polymath Rudolf Virchow “resemble great warning signs.” He was talking about the typhus outbreak in 1948, but Jennifer Learning quoted him in her keynote, marvelling, as she has done before, at the prescience and the relevance.

“War, plague and famine condition each other, and we don’t know any period in world history where they did not appear in more or less large measure either simultaneously or following each other.”

Nothing in a vacuum. Which means that epidemics aren’t just outbreaks of disease – they’re indicators, breakdowns of systems, epidemics of lost control, as Marc Biot found in his baseline survey monitoring drug stock outs of HIV medicines in South Africa.

Nothing in a vacuum. Which means that epidemics aren’t just outbreaks of disease – they’re indicators, breakdowns of systems, epidemics of lost control, as Marc Biot found in his baseline survey monitoring drug stock outs of HIV medicines in South Africa.

An acute crisis in the Eastern Cape in late 2013 caused one of the depot systems to collapse entirely.

“We had to find out if it was a single case or an outbreak,” he explained, of the systematic research that has resulted in joint consultation and the first public-private partnership to create a national Stop Stock Outs Project.

Philipp du Cros, head of MSF’s research arm the Manson Unit, stood up to bring the day to a close. The only way to conclude a day of so much information and controlled emotion was with a recapitulation – and a reaffirming.

“The challenges are long-term,” he reminded the audience, “and it’s a double challenge in this abnormal condition – how can we be better, when we’re also in retreat? Which are the questions that are going to have the highest impact? Which are the methodologies? How can activism, the outrage at a problem, provoke us to do a study that provokes us to more activism?”

The difficult questions need answering, and the imperatives bear repeating.

“Jennifer reminded us that it starts with dignity, the empathy for the humanitarian act. That it’s not just about keeping people alive. It’s about helping them to live.”