The young advocate

What has it been like, shifting from student to junior doctor?

I remember the first time I did a Caesarean section by myself. I walked in and paused at the door – because obviously I’d assisted, but I had now assisted enough to be on my own.

I was 48 hours on call, and I remember walking in, pausing at the door, looking at the team – scrub technician, anaesthetist and thinking I am in charge of this team. I’m responsible for two lives and I have to get this baby out safely.

That’s what makes a surgeon a surgeon – you and your hands, your decisions and actions are responsible for someone’s life. Sometimes two.

Does that ever go away?

By maybe the fourth C-section that weekend I didn’t get that overwhelming feeling. I didn’t have time to be overwhelmed – I had a whole ward to run from c-sections to complicated patients in labour. With time your ability and technical skill grow and with that experience, so does your confidence.

How do you define global surgery?

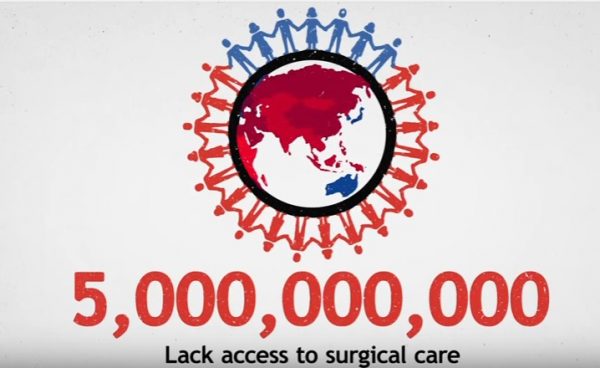

It’s the intersection between public health and surgery – or the public health aspect of surgery, which means different things to different people. Policy, data, research – all that falls into global surgery.

How has it changed since you first got involved?

Well, it’s defined! When I first started out in global surgery there was no baseline data or definition.

Thanks to the Lancet Commission there’s now an academic baseline to what we do, and there’s policy work because of the World Health Organization. The baseline has been set – but we’re still in the opening act. The next stage is getting surgery into national policies – both surgical plans but also incorporating it into Universal Health Coverage.

The big question now is how do you get there.

What’s the role of data in all this?

We can’t do this without data. We won’t know where the gaps are, we won’t know what interventions are most successful, we won’t know what progress is being made.

When I did obstetrics and pedeatrics as an intern I had to collect data. It was expected from my institution, because it was expected by the ministry of health.

But we didn’t collect surgical data for the ministry. And I think the question is how to get to the level where frontline health workers in all settings – but particularly low-resource settings – are all collecting surgical data. They know what the indicators are, and it becomes part of the normal architecture of surgery.

Where does the safety component fit in to global surgery?

Safe surgery is one place that needs a lot of innovation. It needs to engage with people outside of our field. In Kenya we have a lot of ‘hackathons’ where the tech community searches for technology solutions for local problems – imagine if we had surgery hackathons! We could have more safe surgery, using local resources, local innovations. They’re available and they would create jobs, and they’ll help us figure out how surgery looks different in different countries.

I’m not of the idea that we should aim to recreate high-income operating room in low-resource setting. But you need to figure out what good surgery is in all settings – not a compromise on minimum standards but different. How do you do safe surgery without a constant supply of electricity? Because we’re not going to sort electricity just yet but we can innovate around energy supply for critical surgical equipment.

How do you adapt surgery to these settings and keep surgical standards? Because you can’t lower surgical standards. There’s no compromise for that.

Lifebox is developing a new technical programme around reduction of surgical site infection. Do you see much of this at your hospital?

I did my training in two hospitals, a national referral hospital during medical school and a mission hospital during my internship. They were different, very different. In the national referral hospital, a much larger percentage of people got infected, and my take away from that was that there are many factors even outside of the actual surgery – how clean the wards were, quality of nursing care, sanitation in the hospital – all these elements around the surgery ensure there are fewer infections, even in the same country.

And then of course there’s whether the anaesthetist always used the Checklist, which has a window for giving antibiotics one hour before the incision.

It’s a complex system, and it’s important that people realise that to reduce infection the whole system pre, intra and post op needs to be well functioning.

And what do you see as your part in this?

I’m part of the first generation to start global surgery careers from the initial stages of training. So I think a lot of us still don’t know exactly what our future careers look like.

My plan is to become a global surgeon – whatever that means! – so right now I’m trying to figure out how to get a mix of on the ground clinical experience, combined with a policy and knowledge base that can affect policy. It’s an important national issue for me as a Kenyan, but I’m also very passionate about it in an African context and south-south collaboration.

What’s the change in policy you want to see?

It’s a public perception change too – we need to bring the larger population into the journey. To understand that surgery can be made affordable and that as a population it’s in our economic interest for surgery to be made available. The people who normally need it are the ones who are contributing to the economy, so it’s in everyone’s interest for surgery to be accessible and to be safe. Surgery should not continue to be a luxury.

What message did you want your audience at the BeyondBORDERS conference to walk away with?

Now that I’m not a student any more – but as a former student and a trainee – I think it’s important for students to have a voice and pursue their interest in global surgery from the beginning. We’re the ones who are going to become the global surgeons – it’s nice to have the company and a community of those who are practicing global surgery from the beginning of their careers.

So you’re excited about the Lifebox-Medsin Rep Scheme?

Yes! Because it spreads global surgery to the campuses, and finds the future global surgeons – while they’re still young.